Recently, I’ve found myself chatting with friends about masculinity with increasing frequency. Namely, its pitfalls–its implicit codes and constraints and further, its contradictions and violences. I find myself questioning, both internally and externally, if masculinity can truly be reimagined as something different than its historical, commonplace iterations. Broadly, I’m perpetually curious about what masculinity demands of both individuals and larger communities for its existence. My entry point to masculinity as a subject of intrigue is nuanced; as a scholar, my research is centered on masculinity and identity formation. As a trans person, I’ve spent nearly all of my life trying to get my arms around my relationship with this strange, unwieldy force.

When I was younger, my definition of masculinity was painfully simplistic: masculinity was the ‘stuff’ of men; the culture intrinsic to those born male. As an adult, my experiences have greatly complicated this notion.

I emerged from Covid quarantine with a beard and significantly flatter chest, and am now regularly perceived as a man. In my before-gender, (if that’s even a thing?) I still viewed myself as very much masculine (perhaps even more so than the messy bun, painted-nail, cried-after-watching Paddington-Bear version of me that exists today). The difference is, now my masculinity is imbued with the social currency–power, really–granted to those perceived as male. With that power, has come privilege.

As a Black person, my race is always operating as a marginalizing factor in my daily experiences. However, my new embodiment of masculinity, and how others respond to it, has caught me off guard.

A dear friend wrote a poem called “& Somehow Men Are Nicer to Me Now” and it perfectly encapsulates how stark the shift in my experience of gender has been throughout the last couple of years when it comes to my interactions with other men. Men look me in the eye, addressing me directly, despite the woman I'm standing next to having asked the question. They shake my hand and call me things like “boss” and “big man” reflexively. I rarely get spoken over. In casual conversation, my sentiments, however flippant, are met with respect and consideration.

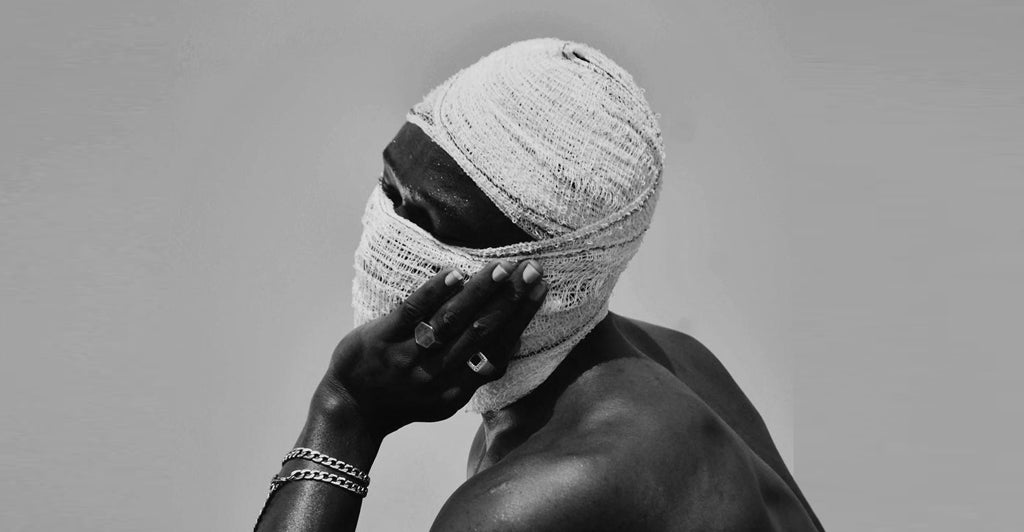

Inversely, my gendered experience has left me feeling somewhat unmoored within my relationships with women and femmes. Sometimes I feel like my masculinity is this massive, immutable barricade between myself and people who don’t strongly identify with masculinity. My facial hair, the broadness of my shoulders, and the bass of my voice–once sources of immense pride for me–now feel like subtle cues of the potential for violence, or at the very least, indications that I exist indisputably outside of the sacred kinship that is ‘the feminine experience’.

The other day, a homegirl of mine attempted to explain her complicated feelings about the importance of closed spaces that are decidedly devoid of masculine-identified people. I understood her perspective, though it made me sad. I remember the glee and fellowship I once felt, rolling my eyes alongside other non-men about how intrusive men and their masculinity were; how they billowed through the room like a bad odor, lingering and looming by their nature. I hated the idea that now, despite my best intentions, my presence might have an identical effect.

“But femme-curated spaces feel safer,” I whined in protest, “dudes just aren’t good at genuine friendship.”

“Why do you think that is?” She countered.

To be honest, I wasn’t sure. As a younger person, I never felt quite integrated into most aspects of what I perceived as femme culture. I contended with a pervasive feeling that I wasn’t ‘girl enough’ to experience the sisterhood I viewed as core to friendships between girls and women. My size, stature, visible queerness, and most notably, masculinity have always been pillars of difference between myself and more feminine peers.

But as much as I could, I attempted to squeeze myself into pockets of girlhood. I marveled at the beauty of femme friendship: cinematic depictions of all-girls sleepovers featured platonic cuddling and heart-to-hearts. The boys I saw in movies didn’t dare touch one another in fraternal affection, or value vulnerability and tenderness in their relationships with one another. The boys I knew in real life used “gay” as a slur. Fortunately, I’ve managed to find lasting connections with friends who were similarly nonconformist to gender norms, but still, I hesitated for years to lean further into masculinity, fearing that it might cost me the few accessible tethers I had to both femme community and my own femininity.

These days, the vast majority of folks that I encounter, across gender and racial identities, have been defaulting to he/him/sir/Mr. terms of address upon meeting me. And for the most part, that feels really affirming. However, at the intersection of Blackness and masculinity, lies a pervasive cultural fear. Black men and masculine folks (and even Black women and femmes, who are often masculinized by the white gaze) know all too well the criminalization and fetishization that undergirds this fear. I have noticed lingering glances, clutched purses– broken out into a cold sweat under the leering eyes of police.

After five months of living just two houses down from her, my neighbor bounded toward me on a rainy day as I pulled up on our street, asking if I was there ‘from facilities’ to repair her storm drain. At a club, I was falsely accused of stealing money from a server’s waste pouch. I turned my pockets inside out to prove my innocence with resignation, already knowing that my locs, beard, and build had been the canvas upon which a fantasy was painted in the mind of my accuser. While the evidence of the cultural capital that masculinity has granted me is hyper apparent, so too is the complex way in which my Blackness is inextricable from any privileges I will ever attain.

Still, for me, the hypothetical pro-con list of embracing my masculinity, and living authentically has infinite tic-marks in the ‘pro’ column. Sure, there is grief, when I think about the prior selves I’ve shed to make room for this current, self-made-man- iteration. There is fear, about how my masculinity will increasingly heighten the anti blackness that I already encounter. Moreover, there are the privileges, no question; some of which make me feel guilty, and fundamentally distant from people with whom I’ve always wanted a greater closeness.

However, in this new embodiment, I have realized that there is in fact a radical potential for masculinity that is not at odds with the rich, tender connections I sought throughout my teenage years. I relish in the idea of revisionist masculinity, realized through new boyhoods and abandonment of antiquated gender norms. I believe in a version of masculinity that isn’t afraid of closeness with other masculine people, or reliant on women and femmes to create spaces that feel safe and nurturing. I try not to allow my masculinity to stop me, or anyone around me, from celebrating softness, and deep, meaningful connection.

The other night, a friend who is also transmasculine came over for dinner. We sat at my dining table, sipped wine, and worked on coloring book pages between giggles. I smiled to myself, and thought, is this what belonging feels like?

|

About the Author: Kelsey L. Smoot is a writer and scholar-poet based in Atlanta, GA |

JOIN THE DISCUSSION (0 comments)